These days, war is swell — at least for the Motion Picture Academy members who choose the Oscar nominees. Of the 10 films on the not-so-short list for Best Picture, two prime contenders, The Hurt Locker and Inglourious Basterds, find their grittiest kicks in the spectacle of men at war: the suicidal heroism they display trying to defuse a Baghdad bomb, the patriotic sadism some American Jewish soldiers show as they scalp men in the Army of the Third Reich. You could say that Avatar is not just a war movie but a call to insurgency against the U.S. military; the long final act of James Cameron’s epic prods audiences to cheer for the bloody victory of Pandorans over American mercenaries. The South African sci-fi adventure District 9 takes the side of illegal aliens — grotty extraterrestrials, that is — against the white humans who have herded them into camps.

11 photos

1. Napoléon (1927, Abel Gance) — the Napoleonic wars

For the most powerful military figure in French history, filmmaker Abel Gance conceived the grandest of all silent-movie dreams: six features chronicling Napoléon’s extraordinary life. He ran out of money and sponsors after just one film, but it’s a beaut, whose restored versions run between 4 and 5½ hrs. Beginning with a snow fight involving the child Bonaparte (war by softer means), embracing his love for Josephine and his irresistible rise through the tumult of the French Revolution, and reaching its climax with the victorious Italian Campaign, Gance’s biopic is as heroic and driven as its subject. The writer-director-producer used wildly swinging cameras to mime the milling chaos of revolutionary life and death, and for the final battle scenes, he sprayed the action across three screens — Cinerama and CinemaScope a quarter-century before their time. Over the years, Napoléon was recut, mutilated and all but lost; film historian Kevin Brownlow devoted decades to reviving it at its original epic length and scope. Francis Ford Coppola showed one version in 1980, with a new score by his father Carmine, and Napoléon triumphed again. That it is not available on DVD in the U.S. is a crime against cinema genius.

2. The Birth of a Nation (1915, D.W. Griffith) — U.S. Civil War

So many superlatives for one picture: the first great feature film, the movie that established the Confederacy as the collective hero of any Civil War film, the biggest box-office hit before Gone With the Wind — and, in its demeaning depiction of American blacks, a racist screed of appalling ignorance and influence. (The film, originally titled The Clansman, helped spur the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan and led to a horrid spike in lynchings.) Put this asterisk next to Griffith’s tainted masterpiece: it was the first great war film. Inventing the

3. All Quiet on the Western Front (1930, Lewis Milestone) — World War I

The aura of nobility — of collegiality among enemies, of jaunty salutes from one aerial ace to his rival on the other side — suffused many of the memorable films about the Great War. Recall the courtly relationship between a German officer and his French prisoners in Jean Renoir’s La grande illusion. In the more realistic, or bitter, movies, the “war to end all wars” simply taught its survivors how to kill millions of young men more effectively the next time. Erich Maria Remarque’s famed novel, filmed by Lewis Milestone, follows a group of young Germans who are seduced by their teacher into enlisting for the patriotism and glamour. Instantly they learn that the hell of war is paved with wretched ambiguities. The main character, Paul (Lew Ayres), shoots a French soldier, then tries desperately, weepingly, to save the man’s life. Paul’s will end — in one of the signature final shots in movie history — as his hand reaches outside a trench to capture a butterfly. Only the butterfly lives.

4. Paths of Glory (1957, Stanley Kubrick) — World War I

Thirty years before his half-brilliant Vietnam film Full Metal Jacket, the 28-year-old Kubrick made this most merciless and clinical of antiwar war movies. It details a suicide mission concocted by the ruthless French General Broulard (Adolphe Menjou): his soldiers must storm a German “anthill” with little hope of taking it and all their lives in jeopardy. When the botched plan fails, enlisted men must pay for the general’s blunders. Three are chosen at random and condemned to death, with a principled colonel (Kirk Douglas) as their only advocate. As commanding officers move troops across a battlefield like toys that can be replaced when they break, so Dax and Broulard debate the fate of the doomed soldiers. Working from Humphrey Cobb’s 1935 novel and a screenplay by two other novelists (sensitive Calder Willingham and hard-boiled Jim Thompson), Kubrick sends his camera tracking briskly through the trenches during the ramp-up to battle, then confines the viewer in closeups with the three condemned men — most notably the weeping, groveling Private Ferod, played by the Method madman Timothy Carey. In the equally insane rules of war, the men must prove their worth by dying for a general’s arrogant stupidity. The road to the firing squad is their path of glory.

5. Das Boot (1981, Wolfgang Peterson) — World War II

Some war movies are admirable for dressing WW II clichés in a new uniform. Das Boot takes another plunge into the black pool of memory and finds — surprise! — flinty nobility. Actually, no surprise for anyone who feasted on the submarine movies of the 1950s. Here is the dogged captain (Jurgen Prochnow), navigating the straits of political bureaucracy and a bungling high command. Here is the wild-eyed wraith of the engine room (Erwin Leder), who “cracks” during one crisis, then performs heroically in the next. Here are the hide-and-seek battles, the claustrophobic tensions, the respect for a valiant enemy. The novelty here is getting the inside German view. Das Boot has thrills aplenty; it moves full speed ahead through its 2½-hr. running time. Of the 40,000 U-boat men in World War II, 28,000 were killed, and the film is careful to emphasize the fatal futility of all this derring-do. Still, the movie holds a lesson for American audiences raised on movies about the beastly Germans. It shows that some of the bad guys were good guys too.

6. Saving Private Ryan (1998, Steven Spielberg) — World War II

From Richard Schickel’s TIME review: “The D-Day landing on Omaha: seasick soldiers massacred the minute the ramps on their landing boats are lowered; other men clambering over the sides trying to avoid the fire, only to drown under the weight of their packs; the surf turning red with the blood of the slaughtered; some who make it to the narrow beach huddling immobilized yet pathetically vulnerable behind what little cover they can find … It makes no difference. Whether you live or die here is entirely a matter of chance, not survival tactics. Spielberg’s handheld cameras thrust us into this maelstrom, and his superb editing creates from these bits and pieces a mosaic of terror. We see as the soldiers see, from belly level, in flashes and fragments, none more vivid than the shot, rendered almost casually, of a soldier staggering along, carrying his severed arm — the struggle against mortality encapsulated in what amounts to a sidelong glance. It is quite possibly the greatest combat sequence ever made, in part because it is so fanatically detailed, in part because the action is so compressed — all that panic in such a tight spot — in part because the horror is so long sustained, for more than 20 relentless minutes.”

7. The Steel Helmet (1951, Samuel Fuller) — Korean conflict

The forgotten American stalemate, which was to U.S. foreign adventures what Pluto is to planets, the Korean conflict didn’t even get the respect of being called a war; officially, it was a United Nations “police action.” Yet more American soldiers went MIA in that 2½-year siege than in the 3½ years of World War II. Sam Fuller, a WW II veteran who later apotheosized his own regiment in 1980′s The Big Red One, made this first-ever Korean War film on the cheap: in 10 days, shooting in Los Angeles’ Griffith Park, using 25 extras whom he choreographed to look like swarming hundreds. Peppering his script with wisecracks about identifying the enemy (“He’s South Korean when he’s running with you. He’s North Korean when he’s running after you”) and bitter jokes about a late officer (“He’s fertilizing a rice paddy with the rest of the patrol”), Fuller took official flak for a scene in which a U.S. officer kills an unarmed prisoner; he was denounced as a communist and investigated by the FBI. That’s a heavy price to pay for a $100,000 movie with million-dollar battle scenes and a cynical worldview that’s … priceless.

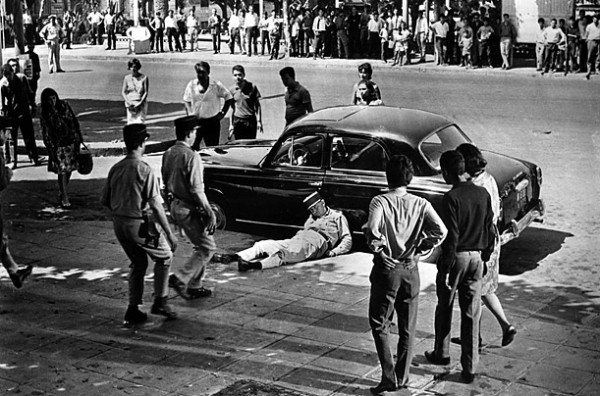

8. The Battle of Algiers (1966, Gillo Pontecorvo) — French-Algerian war

An occupying army will always be outnumbered by a civilian population. When the locals decide that subjugation is a death sentence and that freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose, they can make enough mischief to drive the colonials out. This faux-doc report of the 1954-57 Algerian resistance by the National Liberation Front, and the popular insurgency it stoked against the occupying French, had the revelatory force of a cinematic IED when it opened during America’s Vietnam turmoil. Made by an Italian team but produced by FLN leader Saadi Yacef (and based on his prison autobiography), the film borrows its panoramic narrative and churning style from an earlier reconstruction of an urban uprising, Nanny Loy’s 1962 Four Days of Naples. A canny propagandist, Pontecorvo knew what Hollywood knew: to win an audience�s sympathy for an underclass people, make them beautiful. The Battle of Algiers wins the battle of ideas with Algerian faces that are artfully sculpted and wide, imploring eyes meant to haunt the viewer. The movie certainly left its mark on generations of American officials. Carter adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski called it a must-see for policymakers, and in the summer of 2003, as the Iraq insurgency started exploding, the Pentagon’s special-ops office held a screening of the film. Those in attendance apparently didn’t take its message to heart, and the Bush Administration found that the occupation of Baghdad was a much longer, costlier, deadlier battle of Algiers.

9. Apocalypse Now (1979, Francis Ford Coppola) — Vietnam

The 1970s were the decade of ornery, realistic movies, when filmmakers dared to address topics like government conspiracies, racial animosity and big cities’ fetid decay. Odd, then, that no American in the ’70s made a movie about the war in Vietnam until after it ended. (M*A*S*H doesn’t count; it was set in Korea.) Coppola, fresh off his two Godfather epics and The Conversation, decided to film a John Milius script roughly based on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, about an Army captain (Martin Sheen) cruising through hostile territory into the lair of mad Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando at his most grotesque and gnomic). On location in the Philippines, the crew endured every possible calamity, from monsoons to the leading man’s heart attack. (Sheen recovered.) Presenting an unfinished cut of the film at Cannes, Coppola said he had endured his own private Vietnam. Not that any movie is worth such sacrifice, but Apocalypse Now nailed the madness of Americans lost in a jungle of misguided motives and foreign-policy screwups. Turning Norman Mailer’s question, “Why are we in Vietnam?,” into psychodrama, the film says that only the deranged survive — like Robert Duvall’s macho surfer, proclaiming, “I love the smell of napalm in the morning … It smelled like … victory.”

10. Black Hawk Down (2001, Ridley Scott) — Somalian mission

Most war movies use battle scenes the way musicals use production numbers: several are sprinkled throughout the picture to stir the viewer’s pulse. Not so with Black Hawk Down. After a brief introduction of the main characters, the picture is all fighting, all the time. It’s a 2-hour-plus gunfight at the O.K. Corral, except that the weapons are blazing on the streets of Mogadishu, where all lives are expendable. (President Clinton quickly ended the mission, which was more or less humanitarian.) Scott was criticized for focusing on the white Americans, for turning the Africans into an indistinguishable blur of grenade fodder and for allowing the implication that the deaths of 18 U.S. soldiers held greater import than the 300,000 Somalians who died at the regime’s hand before the military arrived. But if you want to feel the heat and stink of war, to know how desperation kindles gallantry and barbarism, see Black Hawk Down.

0 comments:

Post a Comment